1963

In 1963, I turned eighteen but in some ways still felt like

a kid. As for most teenagers, there had been conflictions (because I knew

better and it was about me), but I didn't take life too seriously and was in no hurry to grow up.

Perhaps my main fear was that I didn't have full control, but to be honest, Mum

and Dad gave me plenty of scope to do my own thing.

I was the oldest kid at home in 1963 because John had moved

to the military college at Duntroon in Canberra. Despite this, there were still

five siblings at home—four boys had been joined by our sister, Janette, who was

born in 1961. (She arrived overnight, because I was ironing my hockey shirt on

a Saturday morning in May, prior to playing in a match for Brighton High

School, when Dad came out bleary-eyed from a sleep-in to tell me we had a baby

sister).

We moved from Woodville North to Glengowrie, near Glenelg,

in the middle of 1959, after Mum and Dad had been sixteen years in the little

fibro house. They'd been saving during that time to build their own home, bought

the block of land at 26 Kipling Avenue, and then built a beaut modern brick

house which was home to me until the end of 1964.

* * * *

*

In 1963 I was enrolled as a student at the Wattle Park

Teachers' College in Kensington, after completing high school and being granted

a scholarship to train as a primary teacher. The scholarship also paid for my

enrolment at Adelaide University as a part-time student and the Teachers'

College allowed me time to do a couple of university subjects per year towards

an Arts degree.

I lived at home during the College years—apart from course

costs the scholarship was not much more than loose pocket money paid

fortnightly and Mum and Dad agreed that I needn't pay them board, for which I

was grateful. At that time I was able

to have various half-days at home because of my time-table, and with the other

boys at school and Jan perhaps having a nap, Mum and I were able to have chats

about everything under the sun, including stuff I was studying like child psychology,

and this is something I've never forgotten.

To get to Wattle Park, I used to walk across to catch a bus

which went up Anzac Highway to the city, switch to a second bus that went up

Kensington Road to the end of the line, and then a short walk to the college.

Occasionally I caught the tram into the city but there was more walking

involved.

After a few months of commuting from the coast to the

foothills via the city, I bought a second-hand Vespa scooter for a few pounds

and used that to commute to College, saving money in fares and about an hour

each way in time. The year before I did some driving lessons in the family car

with Mum as my instructor and then got a driving licence, but I don't remember

ever borrowing the car—I don't think it would have been allowed. Anyway, the

Vespa made me independent.

The Vespa was a two-stroke 150cc Gran Sport, which meant it

had four gears instead of three and more power than the 125cc standard model,

as well as rider and pillion seating in one piece instead of separate seats. I

had it less than two years but had a lot of fun and only crashed it three

times.

The third time was the worst, when I ran into the back of a

delivery van that pulled up suddenly in front of me. I know! It was my fault!

Unluckily, I wasn't wearing my helmet (not compulsory at the time). Luckily, my

head hit one of the small windows in the rear barn doors and broke it, which

meant that instead of being dead from hitting the metal (testimony of ambo), I

spent one night in hospital with concussion.

I learnt fairly quickly how to strip the Vespa down and

perform maintenance tasks. The cylinder head was always coking up with black

soot. The early warning was that the motor would splutter and lose power. I

would shift down through the gears using engine compression to coax the scooter

past parked cars enough to get out of the traffic stream. The immediate

road-side solution was to remove the spark plug and extract the sliver of soot

that closed the spark plug gap, a twenty-minute job. The longer-term solution,

a Sunday afternoon job, was to remove the cylinder head and de-coke it, and

this would be good for a month or so. From being ultra-careful, soaking the

cylinder head in petrol and gently brushing with a toothbrush, I progressed

over the months to scraping ruthlessly and unsympathetically with a large

screwdriver!

One morning, I was on my way to a University English exam

in the city when the Vespa refused to perform according to requirements and I

had to remove coke from the spark plug not once but twice. I was greasy, hot

and bothered, and an hour late for the three hour exam which I had no hope of

passing. One exam question asked for an exposition of "braggadocio"

in literature; I was in such a mood that I seized on this and wrote extensively

in the time available about Tony Braggadocio, a fish and chips shop owner, not

so much a short story as incoherent rambling. I didn't pass the exam.

* * * *

*

When we moved to Glengowrie in 1959 I was in my second year

at Woodville High School and knew many of my classmates from primary school.

The new start I had to make at Brighton High School was traumatic to some

extent, in a new environment, knowing no-one. This was exacerbated by the fact

that the subjects I was studying did not transfer fully to the new school. In

the academic stream I was in, I studied both Latin and History, but at Brighton

these were alternatives; in another time-slot two subjects were offered, but I

wasn't doing either of those. The solution was that I would study History on my

own in the library in that latter time-slot, and seek assistance when

required—I was fourteen at the time—not a recipe for making new friends and

fitting in, but I survived it.

I know now that I should have given up Latin. I loved it

for the Roman history, and translations were like jigsaws or word puzzles,

always a challenge. But I didn't apply myself to the rigour of learning the

intricacies involved. I failed the fourth year exam and had to sit a

supplementary exam in the summer holidays in order to matriculate. My marks

were just good enough to give me a second chance. I vividly remember sitting in

the backyard shed with its corrugated iron roof, sweltering in a heatwave, the

table-tennis table strewn with my Latin books and notes, and the sweat pouring

off me as I laboriously translated Ovid and tried to make my translation sound

poetic. I did pass the supplementary exam, though.

But to top off the story, when I started at University I

enrolled in Latin, convinced that it was an essential foundation of a

well-rounded education! Of course, I failed the exam.

* * * *

*

Settling into Brighton High School and the new

neighbourhood was made amazingly easier by the fact that our street was full of

teenaged boys, with ages spanning a couple of years similar to Peter and me.

Chris lived across the street and was in my home class at school. We became

friends. Jock lived next door to Chris, was slightly younger and didn't go to

our school, but over time he became a closer friend because we had many

interests in common.

In those days we still had no television in our house and

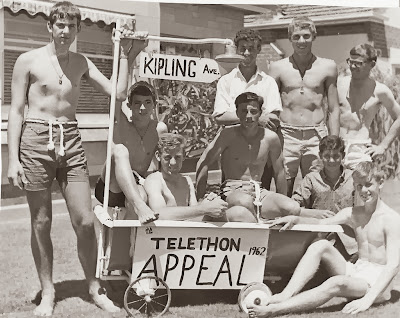

had to keep occupied in other ways. It's not possible to describe how teenage

boys think and dream up weird activities, but we did have a camaraderie exemplified

by the fact that the "Kipling Kids" from our street pushed a bath on

wheels from the Glenelg beachfront to the Adelaide CBD to raise funds for the

Children's Hospital annual appeal.

The photo shows that we were all fashionable in board

shorts despite the lack of surf (or surfboards) anywhere near where we lived.

Jock is on the left, Peter sitting down in the bath on the left and me standing on

the right.

In the last couple of years of high school my interests

were largely non-academic. I played tennis and hockey, and was interested in

cars and bikes, music and the beach.

I had a bicycle while still in primary school and rode to

school for a couple of years even though it was only about 700 metres. Woodville High was about 1.2km south and an

easy ride. My bike was a hand-me-down from John, with no gears and no

hand-brakes, just a coaster hub brake. Before we left Woodville, we made trips

by bike to Henley Beach for swimming, about 10 km, and east to Windsor Gardens

to visit a friend of John, roughly 12km uphill. At the time, these were like

epic journeys to unexplored country even though the distances were not great.

In the summer holidays at Glengowrie, probably in 1961, I

worked in a casual job as an assistant to a truck driver delivering blocks of

ice to caravan parks and customers who had no refrigerator but only an icebox.

With some of my pay I bought a brand-new, two-tone blue Healing bike. It had a

three-speed Sturmey Archer rear hub and handbrakes, quite unfamiliar to me. I

loved it and apart from spending a lot of time cleaning and maintaining it, I

would race as fast as possible to and from school, about 2.5km. The bike meant

that the whole district, from Jetty Road, Glenelg to the Brighton Jetty and

beyond, was accessible to an exploring teenager.

But I was also interested in cars and kept abreast of all

new developments. For several years I used much of my pocket money to buy Wheels

and Sports Car World magazines every month. I had a predilection for

small exotic cars such as the Goggomobil Dart and NSU Printz. For a long time

my favourite car was the Fiat 500 Bambino (I took a photo of a pale-blue one

near the Patawalonga Creek) and I was impressed by the Volkswagen wins in

round-Australia rallies against bigger, more powerful competitors. During

boring lessons at school my doodling was often futuristic car designs.

In 1963 I bought my first car for a few pounds. It was a

1932 Austin Seven tourer. I also bought a second car with an aluminium racing

body for spare parts. The plan was to restore the Austin to its former glory,

with help from Dad. The body was formed over a wooden frame, some of which was

rotten, and I remember that Dad meticulously shaped hardwood replacement pieces

for the curved leading door-frame edges so that the door hinges had something

solid to be fixed into. We sprayed the body British racing green and the

mudguards black. It looked magnificent. However, when I left Adelaide at the

end of 1964 it was still not finished and I gave it to Lester—I never did get

to drive it.

While that was happening, my friend Jock from across the

street bought a huge limousine, an Austin Twelve from around 1929 with leather

upholstery and tons of interior space, and I helped him work on that to restore

it (I said earlier we had similar interests!). I can remember spending Sunday

afternoons in the shed of Jock's grandfather where the car was stored, lounging

in the huge rear tan-leather seat, listening to pop music while refurbishing

brass-work like the massive headlights.

* * * *

*

I began playing hockey at Woodville High School, where the

coach was Gerry Phillips, my Latin teacher. He was an excellent mentor who knew

how to nurture players and went on to become the state men's coach. He taught

me the value of being left-handed on the left side of the field.

Being left-handed, I played left half-back, the theory

being that as the opposing right-winger rampaged down the right flank against

the boundary line, protecting the ball with his body, I could lean across,

while running alongside with the extended stick in my left hand, and steal the

ball with a neat flick of my dominant wrist. Sometimes it worked.

The interest in hockey was not so great when I moved to

Brighton High and I think we coached ourselves. Most weeks we were thrashed by

the other schools. However, I think I was able to pull off the left-handed

steal just sufficiently for my team-mates to think I wasn't such a bad player.

(I forgot to mention that hockey sticks are all right-handed and no-one can

tell if you are left-handed—it's like a secret weapon—in my mind anyway).

I'm second from the left in this photo, playing for Brighton High at West Beach.

At the Teachers' College there were enough of us to form a

hockey team and we played in the district competition. Again we had no coach

and had little time to practise together. We were often short a player and

couldn't take matches too seriously, so we never won. I enjoyed playing in bare

feet which was unconventional, to say the least. It made me feel more nimble

and alert, but was obviously fraught with danger and not viable if the grass

was wet and slippery.

Peter and I began playing tennis while still at Woodville.

There was a tennis club in Thirteenth Avenue, less than three hundred metres

from home and we often went to play after school. After we moved to Glengowrie

we joined the Holdfast Tennis Club, on the eastern side of the Glenelg Oval,

and played matches on Saturday afternoon. I also played some Saturday morning

matches for Brighton High but suspect I was only a fill-in. I like to think

that I had a hard, flat serve, and being left-handed could surprise my

opponent. Unfortunately, my most consistent play was the double fault. It

wasn't long before Peter could beat me all the time and I stopped playing once

I left high school.

* * * *

*

For the last year or so of high school I had a girl friend,

Liz. The peer group I was part of began to pair off for social

occasions—everything from school dances to afternoons lounging around on the

beach—and it was important to not be the odd one out. Being the odd one out was

untenable, given the condescension involved in feigning attention to the odd

one out's riveting conversation while kissing one's girlfriend.

Liz's mother, a single mum, worked on the weekends as a

dancing instructor and sometimes we went into the city to indulge in ball-room

dancing. I learnt the rudiments of the military three-step and the Canadian

barn-dance to the dulcet tones of the twin saxophones of the Billy Vaughn

orchestra, but I never became either adept or enthusiastic.

Without female siblings (until I was sixteen) as role

models, I understood that girls were on a completely different wave-length and

I wouldn't have been the first boy to feel gauche in dealing with the opposite

sex. I can remember the agony of deciding what to buy Liz for a Christmas or

birthday present!

The naughty bits were mostly confined to standing in the

shadows against the huge stone gateposts at Liz's place, after an evening at

the pictures or similar, pressing close and fondling until Liz's Mum, realising

we must be home by now, would call out from the front of the house, end of

story.

While at Wattle Park, I did fall in love once (and she rode

pillion on my Vespa once!) but didn't have a "steady" girlfriend, and

I was involved in groups that didn't necessitate having a partner, so that I

only occasionally dated a girl to go to the pictures or a dance.

In 1963 I joined the college Bushwalking Club, and the Tea

and Damper Club, which was interested in traditional bush music. The membership

of the two groups was intertwined. Activities included meetings where we made

music and had sing-alongs, went on picnics to do the same thing, and went

bushwalking, from day trips to long weekends.

The longest walk I did was a ten-day excursion in the

Flinders Ranges. About a dozen of us drove in a truck to Wilpena Pound. We

carried all our supplies for that period in backpacks and walked west and north

of the Pound to such places as Edeowie Creek and Aroona Valley in a long

circular walk. We relied on finding water on the way, usually at stock watering

points, and once, when one of these was dry, we walked in the dark to find the

next one, rather than walk in the heat of the next day without water. I suppose

we felt like early explorers.

A photo taken on our big walk. Notice the complete lack of any sleeping mats or pillows, only groundsheets.

I started playing harmonica at this time and could play

enough "by ear" to provide some accompaniment to the singing around

the campfire. Incidentally, the Tea and Damper Club (named from a song title)

was started by Graham Jenkin, my senior by a couple of years and teaching at

Coober Pedy in 1963. He wrote some wonderful ballads of his own and did much to

collect old folk songs.

As an aside, in April 1964 a group of us were dropped off

at dusk on Sunday evening in the city after a weekend of bushwalking, weary,

smelly, and covered in dust. On our way to public transport and home, packs on

our backs, we walked past a row of people, extending more than a block,

preparing to camp on the footpath like destitute homeless folk. It transpired

that they were making an early queue to buy tickets to the Adelaide Beatles

concerts!

* * * *

*

At the College I was taught what was considered necessary

to become a primary school teacher—everything from how to teach multiplication

and division to stages in the life cycle of a frog. As well as methodology we

were also given the essential background knowledge. While we were taught the

basics of music theory and notation, we also had to learn a musical instrument.

The default instrument was the recorder—class tuition was provided, and there's

nothing more calculated to turn anyone against music than the sound of twenty

recorders in unison trying to play the same notes.

In my case, I soon enjoyed the thrill of being able to

translate what was in my head to audible music and I was soon attempting (on

the recorder!) jazz standards that I'd been listening to, usually on my back in

my bedroom, but at least once in the College music classroom, to general

incredulity.

Colin Thiele, the well-known author of childrens' books

like Storm Boy, was a lecturer at Wattle Park. I joined his elective

sessions in creative writing. A handful of us met once a week in his office and

discussed work which we had submitted for his criticism. I was writing poetry

at the time, some of which was made available for his comment, and I still

appreciate the advice I received (much of which involved metaphor and similes,

which I don't seem to have adopted very well, but mostly he said to write what

you know). He went on to become vice-Principal and then Principal of the College

after I left.

In the second year of my training, I joined the specialist

group in the Rural Course, learning how to cope with teaching in a one-teacher

school with all grades from one to seven. (I'm proud to say that in my career I

possibly taught in more one-teacher schools than almost any teachers). There

were practice sessions at Netley Primary where several classes were set up as

model one-teacher schools, including lots of sets of siblings as is found in

the bush in a one-roomed school. It took hours to prepare lessons! I worked for

a fortnight at Inman Valley school and boarded on a dairy farm, my first taste

of country living.

We Ruralies saw ourselves as a breed apart, willing to do

the tough stuff, and were usually the same group that were bushwalking and

enjoyed shearing songs. In my case, I couldn't wait to get out of the city. (In

fact I was offered another year at Wattle Park to complete my uni degree, but

rejected it in favour of getting out of Adelaide).

* * * *

*

At the end of 1960 I drove with Mum and Dad to Perth (the

other boys went under John's care on the train). The road from Port Augusta to

Norseman was hundreds of kilometres of corrugated gravel and bull-dust, my

first proper taste of the outback. I loved it and have never forgotten that

introduction. I got my first camera, a Kodak Brownie 127, shortly before this

and I still have a couple of photos from the trip, including one of a

rabbiter's truck filled to overflowing with hundreds of rabbit carcases, taken at Balladonia.

In the summer of 1962-3, Jock and I drove his Ford

"100E" on a coming-of age trip into Victoria. We spent Christmas Eve

in Lorne and New Year's Eve in Lakes Entrance, camping in a tiny tent just big

enough for four with a bit of stacking, if it became necessary (usually not).

Then we travelled north on the Omeo road, a primitive dirt track—Jock scraped

the cliff face once, and further on hit a wallaby—and after a day or so in

Bright we had run out of money, spending more than planned on hangovers, and we

made a beeline for home.

* * * *

*

Up until 1963, my musical interests were almost limited to

pop music. This meant following the "hit parade" or "Top

40" by listening to commercial radio and clipping the "chart"

from the newspaper once a week.

Perversely, I didn't like the mass of pop music—normally my

favourites never reached the top ten. I liked 'proper' rock 'n' roll (my term),

some instrumentals, and the odd song whose lyrics, gimmick or sound made it

stand out from the crowd.

"Proper" rock 'n' roll was always up-tempo with

plenty of heavy rhythm and mongrel vocal, with or without angst. No ballads, no

tin pan alley written for profit. There was She's My Baby (Johnny

O'Keefe), Hippy Hippy Shake (Chan Romero) and Let's Have a Party

(Wanda Jackson). I used to be an Elvis fan in the 1950s but can't think of

anything decent he did in the 1960s.

There were some songs I enjoyed for their quirkiness or

clever lyrics. Multiplication (Bobby Darin) and Does Your Chewing Gum

(Lonnie Donegan) spring to mind.

I was very much into instrumental music (possibly not

having to listen to banal pop lyrics), especially with a bit of panache. Joey's

Song (Bill Haley) probably put me on this track a few years earlier. I can

think of Wabash Blues (The Viscounts), Wonderland by Night (Louis

Prima) or Mexico (Bob Moore), from that time. Surf music soon became the

big craze (taking over from the Shadows). I often rode the Vespa to Somerton or

Seacliff Lifesavers on the beach for the Saturday night dance, stomping the

night away in board shorts. Pipeline (the Chantays) would have been

played every week (along with Apache).

Instrumental music, which included Kenny Ball, Acker Bilk

and Dave Brubeck's Take Five, led to my interest in jazz. By 1963 I was

listening to an eclectic mix of jazz, both live and recorded, from New Orleans

traditional and big band all the way to bebop. I can remember sitting in Jock's

loungeroom, watching his latest LP rotate on the turntable and listening to the

piano of Thelonius Monk. At one point Monk calls out "Quarter tone!

Quarter tone!" Not only did Jock and I discuss at length how this could be

done on the piano but Jock went around for weeks injecting the phrase into any

conversation with suitable American accent.

In 1963 and '64 I loved frequenting the jazz clubs in

Hindley Street and Grenfell Street, downstairs in a tiny setting where you

could almost touch the clarinet player and the sounds were all in and around

your head. I still have a unique compilation LP record pressed on vinyl with

the tracks selected by me from tape recordings of one of the clubs, featuring

bands like the Adelaide Allstars.

My record collection soon included albums by Duke

Ellington, Chris Barber and Zoot Sims; my grandmother, Mum Mort, even gave me a

Gerry Mulligan album for my birthday.

* * * *

*

The joke among Wattle Park Ruralies was that if you applied

to teach in the South-East you would be appointed to the Far North or anywhere

except the South-East (in order to toughen us up). At the end of the course, in

our appointment applications, we were required to nominate three districts in

order of preference. I knew of the Muloorina sheep station from meeting my

predecessor when he came back to visit Wattle Park, and also from Donald

Campbell's presence there when he broke the land speed record on Lake Eyre. On

my application I wrote no district name but wrote "Muloorina", with

no second or third choice.

I think the

Education Department got the message that I was serious. At the end of 1964,

with an appointment slip in my hand, I rushed into the Norwood Hotel, where the

Ruralies were gathered to compare appointments, and screamed that I'd got

Muloorina. Much rejoicing and

celebration.

Thus I turned my back on the city. I left home and began a

long teaching career while I was still nineteen. I spent two happy years at

Muloorina in 1964-5.

This was an attempted self-portrait of the fully-fledged teacher in the flat at Muloorina Station, complete with record player and treble recorder.

* * * *

*

Coming next . . . 1973