Here are my favourite ten books of 2013, selected from about 100

books that I added to the collection and read for the first time. It happens that I've concentrated on Australian

novels this year.

I've read some good non-fiction that hasn’t made it to the top

ten, such as Simon Winchester's Krakatoa, an in-depth study of the

violent eruptions in 1883, and Winchester's superbly accessible writing led me

on to The Professor and the Madman about an incarcerated killer who

spent his days compiling entries for the first Oxford Dictionary. Other non-fiction books I was impressed by

were Tom Standage's The Victorian Internet, about the history of telegraph; The Secret of Life of

Bletchley Park by Sinclair McKay, about WWII code-breaking; and Lawrence

Krauss's A Universe from Nothing—I liked his theory but had trouble with

the detail!

The short-list included some beaut books like Shearing in the

Riverina by Rolf Boldrewood, A Happy Death by Albert Camus, two from

Peter Carey—His Illegal Self and Chemistry of Tears, Richard

Flanagan's The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Graham Greene's The

Man Within. I was also impressed by

Alice Munroe's Short Stories.

But the following books

rated in my top ten for 2013 so let's go…

* * * *

*

1. Patrick White - Happy Valley 1939

Possibly a strange choice for number one but I've gone for the

novelty value that I got out of it. I

read a lot of White this year—all the short stories, I re-read Voss,

finally after 30 years I read A Fringe of Leaves and Riders in the

Chariot from front cover to back. And now White's first novel Happy

Valley.

White was in his twenties when he wrote Happy Valley and

had been living the life of a jackaroo in the Monaro country. He obviously knew a fetlock from a

forelock. It is obvious too, that he

enjoyed writing this book and was pleased with the outcome. His powers of observation and his ability to

express what he experienced were incredible, and on show in this first

work. Imagine if I'd set out to write a

book about Muloorina, and then read Happy Valley!

To me the interplay between the characters of different class

reflected in the small-town pecking order show understanding and maturity well

developed already in this first book.

The pace of the novel is varied and reflects the moods of non-urban

living.

It was no longer winter at Happy Valley. You began

to wonder if it could ever be anything else, and there was really no reason why

it should, why Happy Valley should take part in the inevitable time process

rather than stay concealed in some channel up which either time or circumstance

had forgotten to press. Then it happened when you forgot to wonder.

* * * *

*

2. Alexis Wright - Carpentaria 2006

This book won the Miles Franklin award in 2007 and I should have

read it sooner. There is no doubt

Wright is a major writer with much to offer from an Indigenous perspective.

This book is set in her country in fictional Desperance on the

Gulf of Carpentaria, where inevitable conflict occurs between white residents,

two separate fringe camps, a mining development and the forces of law and

order. The overall physical environment

is so strong in Wright's writing I could feel the dust in my eyes, and several

of the themes, particularly fish and fishing, are unforgettably treated. This

is not the tropics of New Guinea or Bali, but the tropics of the Top End—dry,

sparse and hot, no shade but plenty of dust, every footfall is an effort and

there's always sweat. Will Phantom and

the other fishermen have intimate knowledge of tradition; the estuaries, creeks

and gulf; tides, the wind and weather; and the myriad varieties of sea-life and

habitats.

I love the colloquialisms and nicknames, even place names, that

Wright invents or uses. The main

character is Normal Phantom, the policeman is Truthful and a religious zealot

is Mozzie Fishman; the "suburb" of the Phantom family is Pricklebush,

the mine is Gurrfurit. Wright's

knowledge of the idioms and language are impressive.

…government people, important people, money people,

nuisance bugger people, anyone who can take your thoughts away on pieces of

paper, just like that, and put it, wherever they like, inside white man’s

technology in whatchayougoinama

call it? Computers. Yes, that’s the one the old blackfella man had been

tinking about, racking his brains for it: ‘It come to my head for a look

around.’ Yeah! Alright. ‘They lock em up all the information inside for them

own eyes only.’

* * * *

*

3. Thea Astley - The Well Dressed Explorer 1962

Another one of my favourite Australian authors where I went

searching during the year to see what I'd overlooked in the past. I found this.

Astley's first novel and her first Miles Franklin winner turned

up, but only just—I could only acquire a second-hand copy on eBay which I scanned

to make an e-book in case anyone wants a copy.

It was worth the effort.

George Brewster is the central character and his life from

childhood until death is portrayed. He

was never able to overcome the lost love of his childhood, but spent his life

trying, and giving up, and moving on, from the Darling Downs of Queensland to

Sydney. He became a journalist and we

follow not only his career, but the language development, and the clichés of

the trade, that changed as George aged.

Mix in all the religious uncertainties, the infidelities, the striving

for self-delusion, and we begin to understand the term "explorer" in

the title.

The twenty-five-year-old heart discovers in the

glass the fifty-seven-year-old face with all the mutilations and barbaric

developments of five decades. The mottled hand trembles some mornings as it

draws razor along a pleasingly clean path of skin through the lather. Hairs

tuft from ears and on the end of nose, and, captured in the morning sun’s

cruelty, grey ones shock the dark. The white sagging face is sick, is elderly,

is cheerfully insolent about it all, purses its lips and whistles corn.

* * * *

*

4. Lloyd Jones - Mister Pip 2006

I loved this book. My

favourite Dickens is Great Expectations, and of course the setting of a

village school in New Guinea is familiar to me. Mr Watts lives in a remote village on Bougainville during the

1990's mining conflict when the village school put out of action by rebels. He volunteers to keep the school open using

the one text still available, Great Expectations. The novel is narrated by Matilda who

uses Dickens in her growing up, working out relations with her separated mother

and father, comparing the old village with the "new" world of

Dickens' London and her relations with Mr Pip, aka Mr Watts. On top of all this the village copes with

depradations of rebels and rambos.

Around dawn we heard the redskins’ helicopters pass

over the village and then return. They hovered in the air like giant

dragonflies, peering down at the clearing. They saw a line of abandoned houses

and an empty beach because we had cleared off. Everyone. The old people. Mums

and dads. The kids. And those dogs and chickens that had names.

Once again I was struck by the authenticity of the physical

surroundings but more particularly the village life and relationships of the

characters involved. There is no

detachment in small village life but rather full engagement which Lloyd Jones

understands and appreciates fully.

* * * *

*

5. George Orwell - Coming up for Air 1939

If Patrick White is my favourite author it's not by much more

than a whisker, and I can't believe there were books by George Orwell that I

hadn't read until this year. I made

amends by reading his essays and three novels, Keep the Aspidistra Flying,

The Clergyman's Daughter and Coming up for Air.

The latter is about "mid-life crisis", the

pointlessness of dead-end work and futility of trying to rediscover old haunts

and times. It is not depressing but

more an honest appraisal of the way things are. Set in provincial England around 1930, Orwell also has the sense

that things will get worse before they get better. His writing is political simply from the choice of subject

matter. The hero is an ordinary

forty-five year old leading an ordinary life, but with the nous to analyse it.

When you've time to look about you, and when you

happen to be in the right mood, it's a thing that makes you laugh inside to

walk down these streets in the inner-outer suburbs and to think of the lives

that go on there. Because, after all,

what IS a road like Ellesmere Road?

Just a prison with the cells all in a row. A line of semidetached torture-chambers where the poor little

five-to-ten- pound-a-weekers quake and shiver, every one of them with the boss

twisting his tail and his wife riding him like the nightmare and the kids

sucking his blood like leeches. There's

a lot of rot talked about the sufferings of the working class. I'm not so sorry for the proles myself. Did you ever know a navvy who lay awake

thinking about the sack?

* * * *

*

6. Michelle de Kretser - Questions of Travel 2012

The 2013 Booker Prize winner is a tour de force (with the

emphasis on tour?) with many levels and nuances. Laura travels extensively and lands a job in Sydney writing for a

travel guide publisher, Ravi lives in strife-torn Sri Lanka and yearns to

travel. I was most impressed by the

descriptions of Ravi's situation in Sri Lanka, and the brutality in the midst

of down-town commercial normality.

One night, a little further down the coast, the

incoming tide had brought what seemed to be a collection of colossal turds. The

sun, creeping up on the array, revealed bodies from which the heads and limbs

had been removed.

Ravi was the kind of person whose heart contracted

at the sight of a frog-shape mashed into the road. But dailiness normalises

everything, even slaughter. And Ravi was young—what he feared wasn’t extinction

but exclusion. He was haunted by the sense that he was witnessing the birth of

a new world. A digital revolution was gathering speed. He ached to be part of

it. Soon it would transform the way everyone lived, he told Malini; its power,

located everywhere and nowhere, would exceed armies. He used a word that had

become fashionable: global.

De Kretser asks Australians to look at asylum seeking from a

broader perspective than merely political, and the local Sydney scene is

portrayed. At another level,

communications and global travel are explored in the internet age and the

implications for humanity, bringing the haves and have-nots into ever closer

relationships.

7. Carrie Tiffany - Mateship with Birds 2012

This is a beaut little book about how real people behave in real

life, and kookaburras. It has teenagers

in love and "mature" people, Betty and Harry, heading in the same

direction, but most of all it has the wonderfully observed rural landscape of a small farm on the

outskirts of a 1950s country town, with the natural rhythms and changes that occur in a year among the stock, birdlife,

paddocks and daily occupations.

In dairy country it gets dark from the ground up.

The pasture, the mud on the laneways, the wetness of the land, rise to meet the

linen skies. The daylight fades; then it fades again. The trees drip their

black leaves; the last screech of the cockatoos. Harry stayed outside as long

as he could, until the ground was murky and his feet were no longer visible. He

walked cautiously in case he stumbled; his weight held back at the ankle.

After four years with the alpacas at Wiseleigh, I can relate to

every word.

* * * *

*

8. Peter May - The Blackhouse 2011

In the detective mystery genre, this is first of the Lewis

Trilogy, set on the island of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. The book is most memorable for its depiction

of the island with its anachronistic customs and centuries' old

traditions. I read the next two books

in the trilogy and the above comment holds, but the plots are somewhat weaker

or repetitive. The description of the

annual guga hunt when a dozen men spend a fortnight on a remote island

to kill and butcher for meat thousands

of young seabirds in the traditional ways is absolutely unforgettable (and I respect those involved).

On ground as flat as they could make it, right next

to the top of the chute, the two men spread out tarpaulins and laid the salted

birds in a large circle, feet turned towards the centre, the outside flap of

skin folded up to prevent leakage of the pickling fluids created by the salt. A

second circle overlapped the first, and a third overlapped the second, moving

closer to the centre until the entire first layer had been formed. A huge wheel

of dead birds.

The farm crofts that are centuries old were first made of black

stone and are now called blackhouses to distinguish them from the crofts that

more recently used lighter stone. It is

the indelible world of Lewis that makes this book unforgettable, and there's a

detective in there too!

* * * *

*

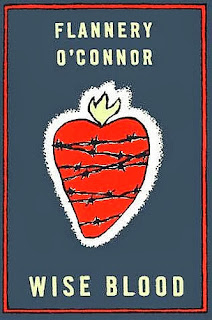

9. Flannery O'Connor - Wise Blood 1949

Her first novel, this is a black satirical work that draws on

the propensity of Americans to believe almost anything and suffer for it. The returned war veteran, Hazel Motes,

starts a street church in the mid-west to make a living, intending to preach

atheistic themes. He is successful enough to provoke a rival who founds the

Holy Church of Christ Without Christ, and then it's no holds barred, and it

turns out Hazel's head is mostly the problem.

O'Connor says in her introduction

That belief in Christ is to some a matter of life

and death has been a stumbling block for readers who would prefer to think it a matter of no great consequence. For them Hazel

Motes' integrity lies in his trying with such vigor to get rid of the ragged

figure who moves from tree to tree in the back of his mind. For the author

Hazel's integrity lies in his not being able to.

* * * *

*

10.Markus Zusak - The

Book Thief 2006

This is the moving story narrated by Death, of Liesel Meminger,

a girl in Hitler's Germany involved in the protection of a Jew in the family

cellar. She becomes a book thief, learns

to read and become a story-teller to fill the long days and nights of

seclusion. The writing is engaging and

lively as Death involves the reader in his to-ings and fro-ings but it is

forthright rather than morbid.

I am in all truthfulness attempting to be cheerful

about this whole topic, though most people find themselves hindered in

believing me, no matter my protestations. Please, trust me. I most definitely

can be cheerful. I can be amiable. Agreeable. Affable. And that’s only the A’s.

Just don’t ask me to be nice. Nice has nothing to do with me.

There's an Australian connection coming from the fact that Liesel survived the

war and went to live in Sydney.

* * * *

*

No comments:

Post a Comment